This page brings together all Edexcel A-Level Economics 8-marker questions on macroeconomics that we could identify from published past papers. These questions are ideal for practising concise evaluation, as 8-markers are the lowest-mark questions where you are required to weigh up arguments rather than simply define terms or calculate values.

If you are also revising longer evaluative questions, you may want to practise alongside Edexcel A-Level Economics 12-marker Past Paper Questions on Macroeconomics and Edexcel A-Level Economics 25-marker Past Paper Questions on Macroeconomics, which test the same content at greater depth.

What is assessed in Edexcel Macroeconomics 8-marker questions?

Macroeconomics in Edexcel A-Level Economics focuses on the performance of the economy as a whole and the role of government policy in managing economic outcomes. Common themes that appear in 8-marker questions include inflation, economic growth, unemployment, fiscal policy, monetary policy, government debt, and trade-offs between macroeconomic objectives.

Many of the questions on this page overlap directly with topic-specific revision areas such as inflation and government debt, spending, and taxation, making this list useful both for exam practice and targeted topic revision.

How to answer Edexcel A-Level Economics 8-marker questions

To score highly on an Edexcel Economics 8-marker, you should make two clear points that directly address the question and meet the assessment objectives:

- Knowledge (2 marks): define key terms or identify relevant economic factors

- Application (2 marks): use data or contextual information from the extract

- Analysis (2 marks): explain the causal link between your factor and the outcome

- Evaluation (2 marks): provide a brief counter-argument or limitation

Unlike 12- or 25-mark questions, 8-markers reward precision rather than breadth. Each point should be tightly written, logically structured, and explicitly linked back to the question.

How this page should be used

This resource is designed to help you practise exam-style macroeconomic evaluation efficiently, without having to search through multiple past papers. You can work through the questions in timed conditions or group them by topic to support revision of specific areas of the Edexcel A-Level Economics specification.

All questions below are reproduced for educational purposes and remain the intellectual property of Pearson Edexcel.

Question 1: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 November 2021 Paper 2

Extract A

Rwandan tariffs on imports of used clothing

In a market in Kigali, Rwanda’s capital, an auction is under way. Sellers offer crumpled T-shirts and faded jeans; traders argue over the best picks. Everything is second-hand. A Tommy Hilfiger shirt sells for 5 000 Rwandan francs ($5.82); a plain one for a tenth of that. Afterwards, a trader sorts through the purchases he will resell in his home village. The logos hint at their previous lives: Kent State University, a rotary club in Pennsylvania, Number One Dad.

These auctions were once twice as busy, but in 2016 Rwanda’s government increased import tariffs on a kilo of used clothes from $0.20 to $2.50. Now many traders struggle to make a profit. The traders are not the only ones who are unhappy. Exporters in the US claim the tariffs are costing jobs there. In March, the US President warned that he would suspend Rwanda’s tariff-free access to US markets for its clothing exports after 60 days if it did not remove the tariff.

Globally, about $4 billion of used clothes crossed borders in 2016. The share from China and South Korea is growing, but 70% still come from Europe and North America. Many go to Asia and eastern Europe, but Africa remains the largest market. The trade enables poor people to afford clothes and creates retail jobs. However, governments worry that the trade undercuts their own clothing manufacturers.

Second-hand imports of clothing now dominate African markets. Researchers at the Overseas Development Institute, a British think-tank, estimate that Tanzania imports 540 million used items of clothing and 180 million new ones each year, while producing fewer than 20 million itself. African manufacturing is weak for many reasons, from ineffective privatisations to collapsing infrastructure. But second-hand clothing imports are a major factor: it is estimated that they accounted for half of the fall in employment in the African clothing industry between 1981 and 2000.

For example, a clothing factory in Kigali is operating at only 40% of capacity and employs 600 workers, down from 1 100 in the 1990s. It is hard to compete, says Ritesh Patel, its manager, when a used imported T-shirt sells for the price of a bottle of water. Instead, the company specialises in uniforms for police, soldiers and security guards, which cannot be bought second-hand.

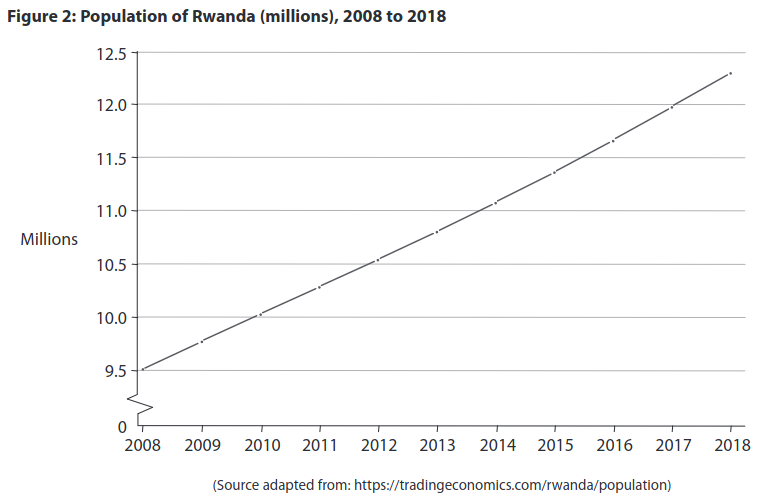

The threatened suspension of tariff-free access to the US market would hurt Rwanda, but not very much. Last year Rwanda sold just $1.5 million of clothing to the US. Nor, with about 12 million people, is Rwanda a big market for US exports

Extract B

Development in Rwanda

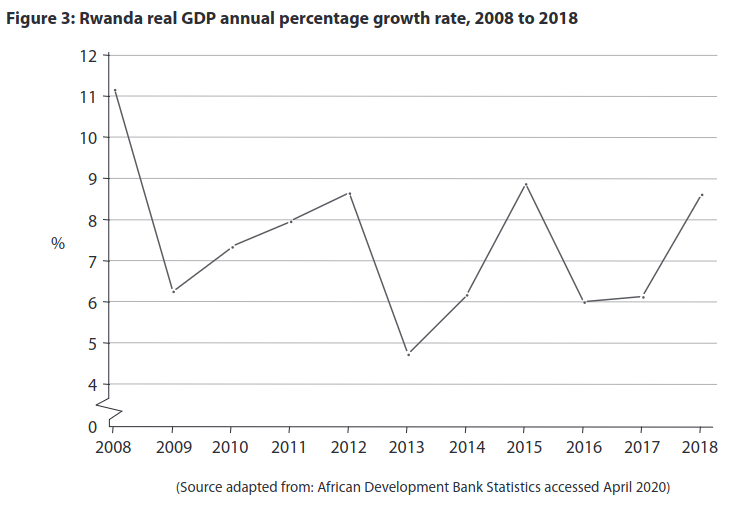

Rwanda’s strong economic growth has been accompanied by substantial improvements in living standards, with a two-thirds drop in child mortality and near-universal primary school enrolment. A strong focus on policies to encourage industrialisation and poverty reduction initiatives have contributed to significant improvements in access to services and human development indicators. Absolute poverty declined from 59% to 39% of the population between 2001 and 2014 but was almost stagnant between 2014 and 2017. The official inequality measure, the Gini index, declined from 0.52 in 2006 to 0.43 in 2017.

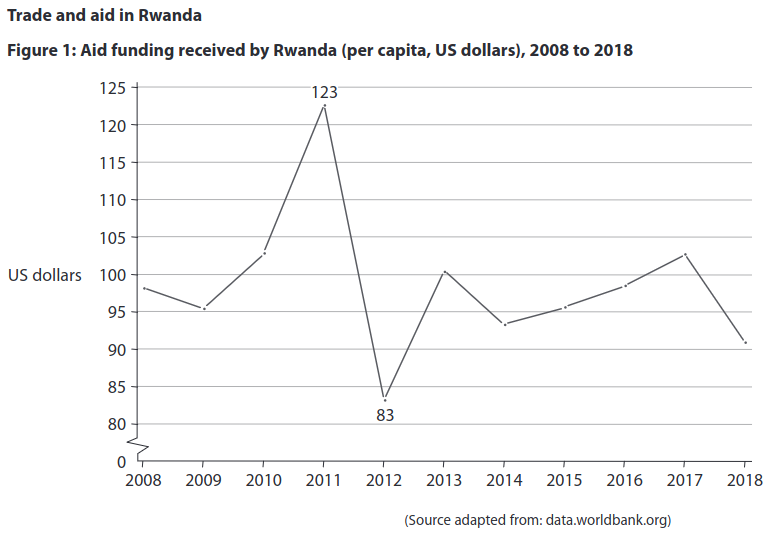

(b) With reference to the information provided, examine two likely benefits for the Rwandan economy of the growth in the country’s population. (8 points)

Question 2: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 November 2020 Paper 2

Extract A

Cheap cocoa is costing farmers dear

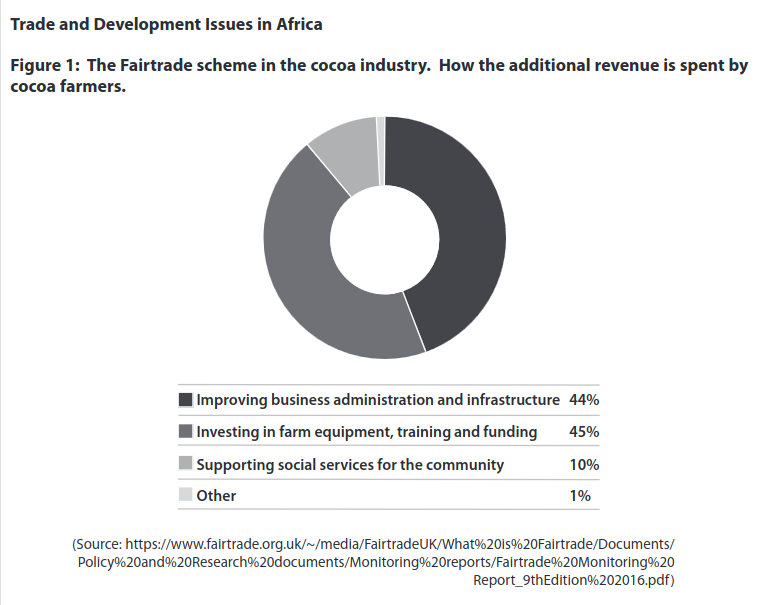

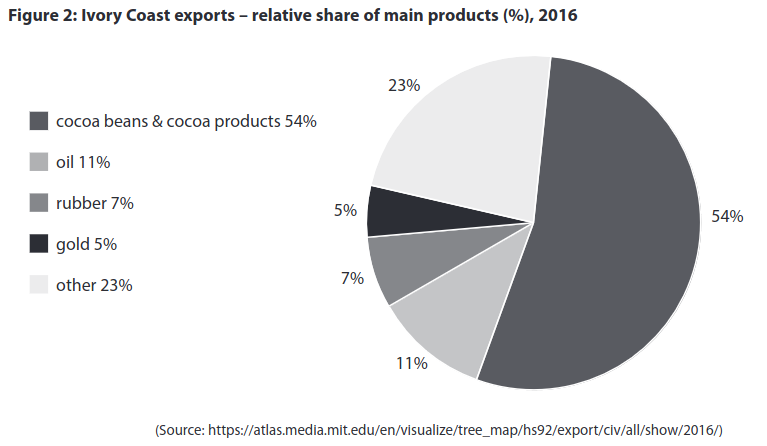

The median annual income of cocoa farmers in the west African country, Ivory Coast, is just US$2 600. Research suggests that an annual income of US$6 133 is needed for this country’s farmers to have a decent, living income. This situation is even worse for farmers who are not part of a Fairtrade scheme.

World cocoa prices fell by more than a third in 2017. Cocoa farmers have to accept all the risk from price volatility, putting a significant strain on their fragile incomes. On the other hand, cocoa processors and chocolate manufacturers are able to adapt or even make high profit and consumers continue to enjoy their chocolate.

This is still happening despite considerable investment in agriculture to build a sustainable cocoa sector. The focus has been on raising productivity and diversifying crops. The average cocoa farm in the Ivory Coast produces only around half of the output that could be achieved with training and resources such as fertilisers, equipment and replanting. If farmers diversify into other crops, livestock or non‑farm activities, they lower the risk they face of fluctuating world cocoa prices.

Even tripling farm output would not provide the average cocoa farmer with a living income. Diversification alone will not always make farms more profitable. If we want farmers to earn a living income, we must also be willing to pay farmers more.

Extract B

Sub‑Saharan Africa is becoming more integrated

After two years of negotiations, representatives of a large number of African countries signed the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) in Kigali on March 21, 2018. This created a trading bloc of 1.2 billion people with a combined gross domestic product of more than US$2 trillion. The agreement committed countries to removing tariffs on 90% of goods and to liberalise services.

This can be seen as a sign of rapid and steady regional integration. Sub‑Saharan Africa in particular is much more integrated today than in the past. The level of integration in sub‑Saharan Africa is now similar to that in the world’s other developing and emerging market economies.

However, the two largest African economies, Nigeria and South Africa, refused to sign the agreement. Nigeria’s manufacturers and trade unions are concerned about the potential negative impacts of becoming more open to imports from other African countries with lower labour costs.

Greater interdependence can expose small economies to their partners’ recessions. After nearly 20 years of strong economic activity, sub‑Saharan Africa experienced the downside of integration in 2015. The collapse in commodity prices and the slowdown in economic activity in Nigeria and South Africa contributed to sub‑Saharan African growth slowing sharply. Since 2017 growth has begun to recover. The recovery is mixed, though, and it is unclear to what extent the slow recovery of the larger economies is still affecting the rest of sub‑Saharan Africa.

(b) Examine two ways, apart from Fairtrade schemes, in which cocoa farmers could boost their incomes despite the falling price of cocoa. (8 points)

Question 3: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 May 2019 Paper 2

Extract A

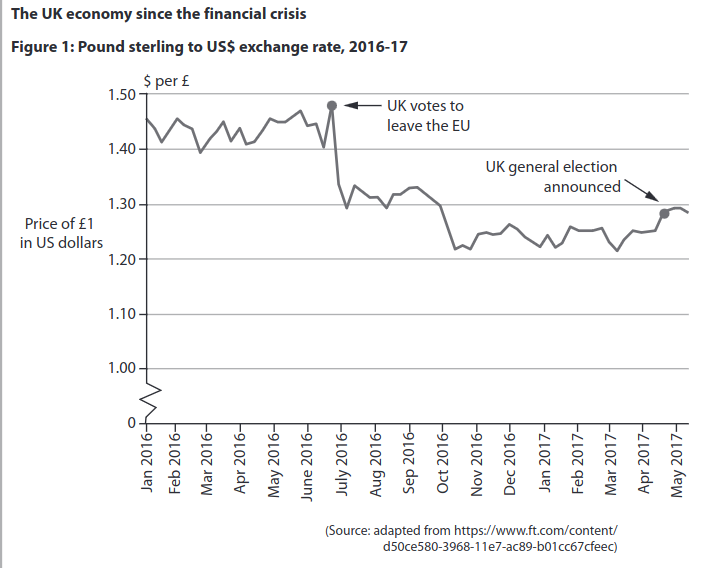

UK companies use forward currency market

The Norfolk-based picture frames maker Nielsen Bainbridge recently made forward contracts in the foreign exchange market to reduce the impact of currency fluctuations. The pound’s post-Brexit referendum depreciation has been a test of nerve for Nielsen Bainbridge and many other importers. At present the company’s suppliers are located in Europe or China. “Currency therefore has a big impact on our business and the margins we can obtain,” says Ms Burdett, the Finance Director. Forward contracts enable institutions, businesses and individuals to lock in an exchange rate over a certain period of time regardless of how the rate moves during that time. Ms Burdett buys currency as soon as Nielsen Bainbridge confirms a large order as a way to fix costs. One third of UK business managers are considering shifting from EU to UK suppliers.

(b) With reference to Extract A and Figure 1, examine the likely impact of the change in the sterling exchange rate on the UK economy. (8 points)

Question 4: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 June 2017 Paper 2

Extract A

European Central Bank disappoints markets with weaker than expected stimulus

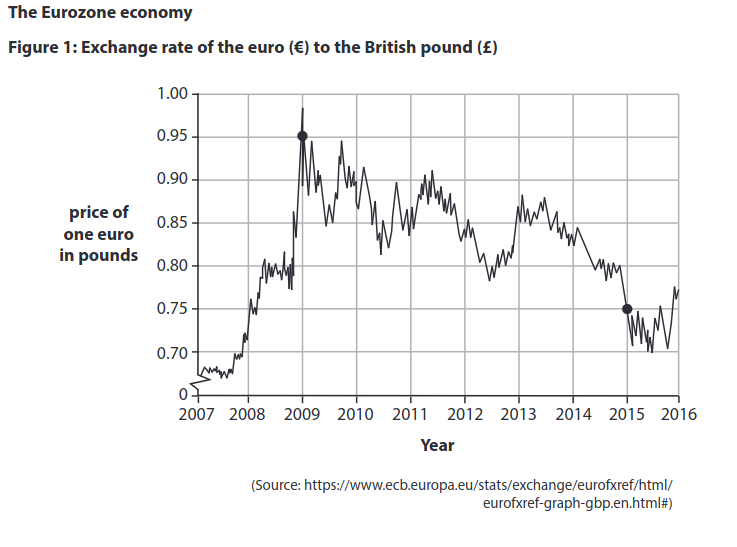

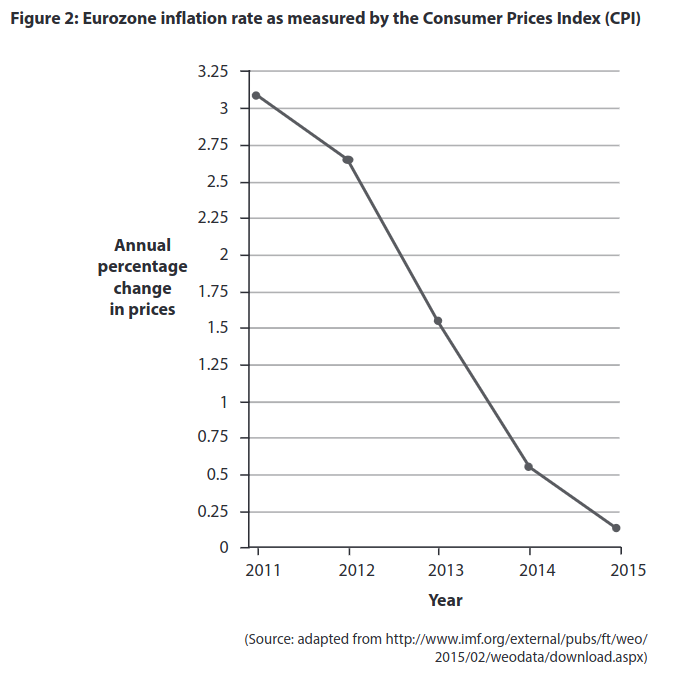

Mario Draghi, president of the European Central Bank (ECB), surprised financial markets in November 2015 with a less ambitious package of monetary stimulus than many had anticipated.

The ECB cut its base interest rate by 0.1% to minus 0.3% in order to encourage private banks to lend funds to companies and households rather than deposit them at the central bank. The central bank agreed to extend its €60 billion (£45 billion) monthly bond-buying quantitative easing (QE) programme for a further six months. The ECB’s €1.1 trillion QE scheme had originally been due to end in September 2016.

“We are doing more because it works,” Mr Draghi said. Yet the ECB did not increase the size of its monthly asset purchases and also disappointed those expecting that it would cut interest rates more aggressively.

The euro rose almost 3% against the dollar to $1.08 after the announcement. Italian and Spanish bond yields both jumped by 0.27% to 1.62% and 1.72% respectively. The ECB’s economists reduced their inflation forecasts for the next two years. They now predict consumer prices in the Eurozone rising by just 1% in 2016 and 1.6% in 2017 – still below the central bank’s ceiling of 2%. In November 2015, the inflation rate was just 0.1% and core inflation, excluding volatile items such as fuel and food, dropped to 0.9%.

Mr Draghi stressed again that monetary policy alone could not restore the Eurozone to economic health. He called for looser fiscal policy among member states to support aggregate demand and more rapid implementation of supply-side reforms. “In order to reap the full benefits from our monetary policy measures, other policy areas must contribute decisively,” he said.

(b) With reference to the information provided and your own knowledge, examine two factors which might explain the change in the rate of Eurozone inflation as shown in Figure 2. (8 points)

Question 5: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 November 2020 Paper 3

Extract A

Can Turkey’s central bank avoid another rate rise?

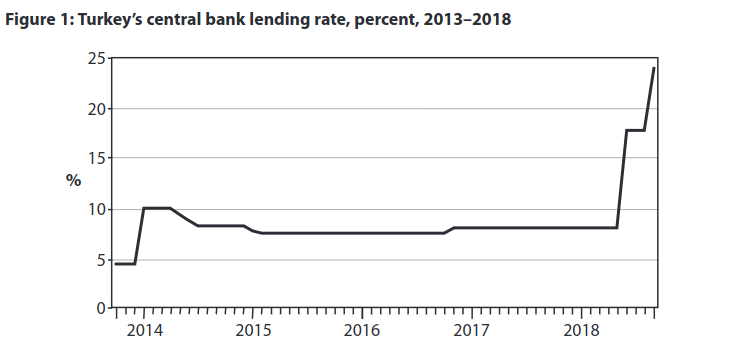

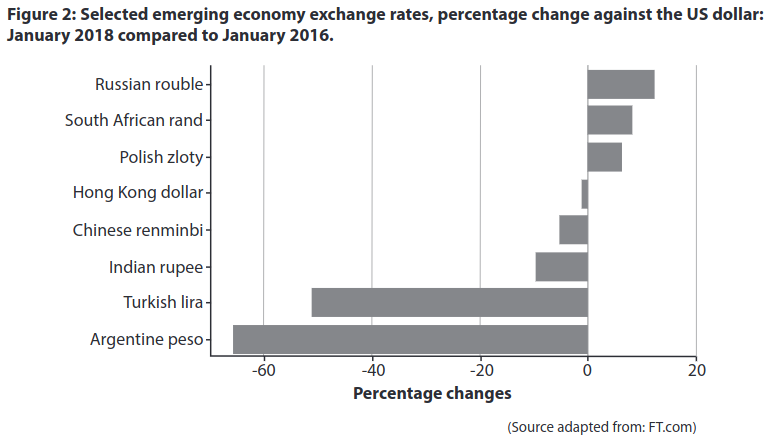

At an annual rate of 25%, Turkey’s inflation is alarming. However, it may have peaked. This may be a turning point for the economically struggling country, whose currency (the Turkish lira) has lost nearly a third of its value against the US dollar in 2018. The central bank may be able to avoid tightening monetary policy further, as a severe economic adjustment is already well under way. Turkey is highly indebted in foreign currency. The Turkish government takes measures against excessive appreciation or depreciation of the Turkish lira to reduce financial stability risks. The financial market faces difficulties in trying to restore foreign investors’ confidence.

Consumer prices increased by 2.7% in October 2018, a much lower rate than the 6.3% recorded in September 2018. The lira has stabilised, having risen 16% since the central bank raised interest rates by 6.25 percentage points. However, the government wants lower borrowing costs to fuel credit growth and economic expansion. Timothy Ash at a London investment bank says at this point it’s “illogical” to raise interest rates again in Turkey. That’s because Turkey’s economy is already experiencing a severe slowdown.

In the long term Turkey’s economic growth is expected to be above that of other emerging markets such as Brazil, Russia and China. Turkey’s private sector is resilient. Between 2018–50 we expect Turkey to grow by an annual average of 3.1%. Brazil is expected to grow by an annual average of 2.1%, Russia by 1.6% and China by 2.8%. GDP growth will nevertheless be well below that recorded in 2004–07 and 2010–15. Average growth in GDP per head will be substantially lower, mainly reflecting the expected rise in the total population.

(b) Examine two reasons why the Turkish government may want to avoid a significant fall in the exchange rate of the Turkish lira. (8 points)

Question 6: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 November 2020 Paper 3

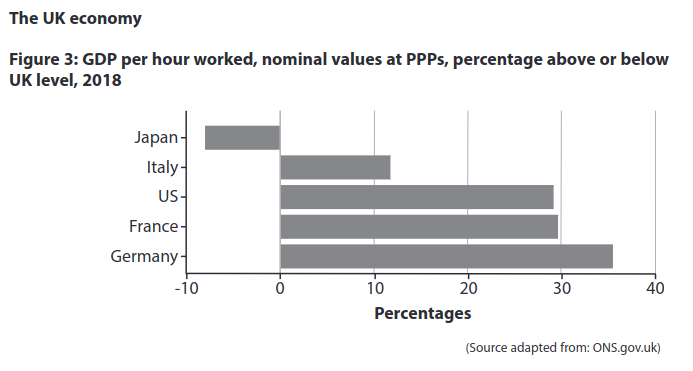

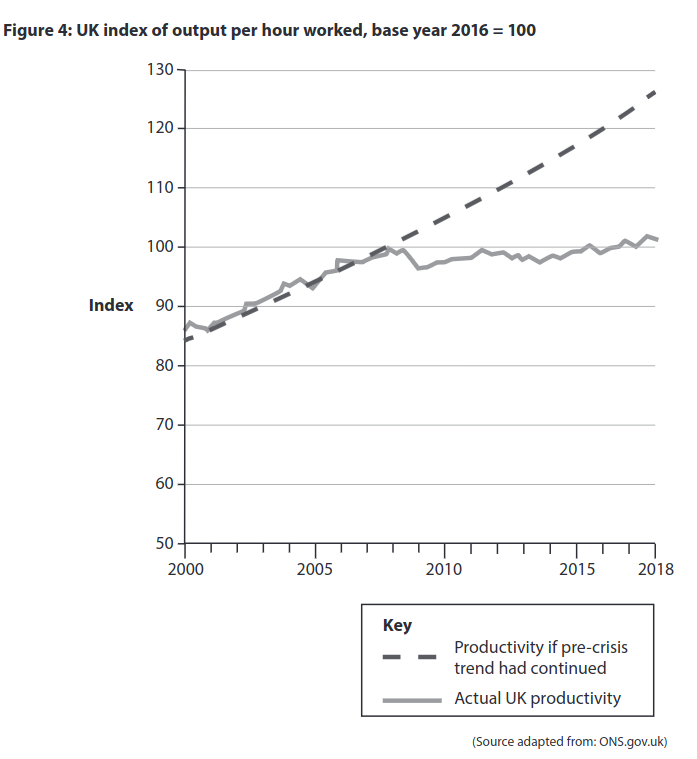

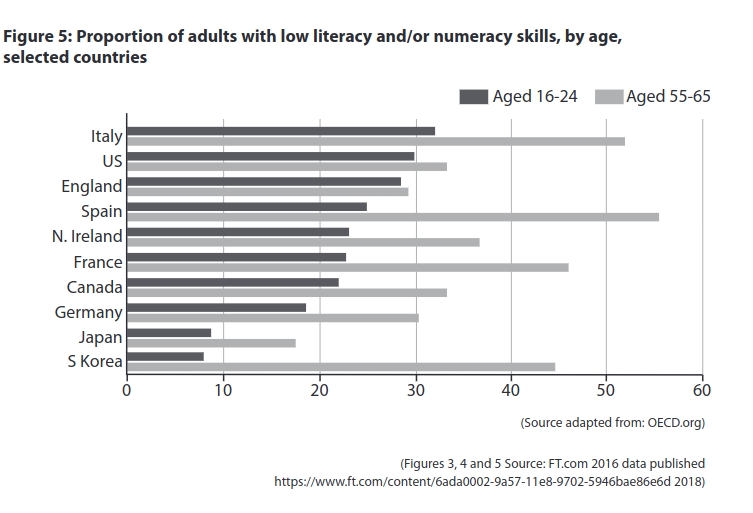

(b) Apart from literacy and numeracy skills in young workers, examine one reason for the trend in productivity in the UK, over the period shown in Figure 4. (8 points)

Question 7: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 June 2019 Paper 3

Extract B

Taxing HFSS foods and subsidising healthy eating widens inequality

Since low-income groups spend a higher proportion of their income on food and tend to eat less healthily, they are the main targets of taxes on products that are high in fat, salt or sugar (HFSS). Subsidies on healthy food are seen as an alternative policy approach to encourage healthy eating. While data on the impact of such policies are scarce, a recent study on the distributional impacts of HFSS taxes and healthy food subsidies found that these actually widened health and fiscal inequalities. The policies tend to be regressive and favour higher-income consumers. Taxes on unhealthy food increase prices which have a greater impact on low income groups rather than higher income groups. Lower income groups prefer to buy HFSS food.

Subsidies encouraged all income groups to buy more fruit and vegetables. However, those on higher incomes proved more responsive and the average share of budget spent on healthy food actually increased for the higher income groups who were more likely to buy the subsidised healthy food and then spend the savings they had enjoyed on yet more healthy food. The diets of the higher income groups before the subsidy tended to be healthier. The choices of the higher income groups are more responsive to price changes. By contrast, lower income groups, if they responded to lower prices, often used the money saved to buy unhealthy items or something else entirely. The long-term benefits of a healthier diet are harder to grasp for consumers when information gaps exist. Often the immediate boost of a tasty treat is more appealing. Taxes and subsidies do not change that. Other strategies are needed to promote healthy eating, especially education.

(b) Apart from changes in indirect taxes and subsidies, examine two causes of income inequality within a developed economy such as the UK. (8 points)

Question 8: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 June 2017 Paper 3

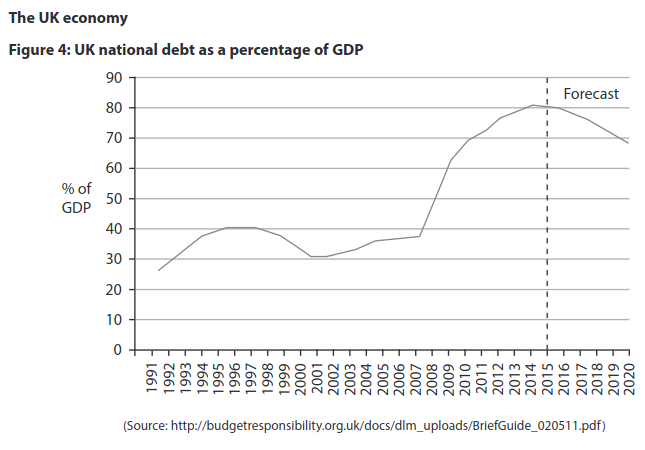

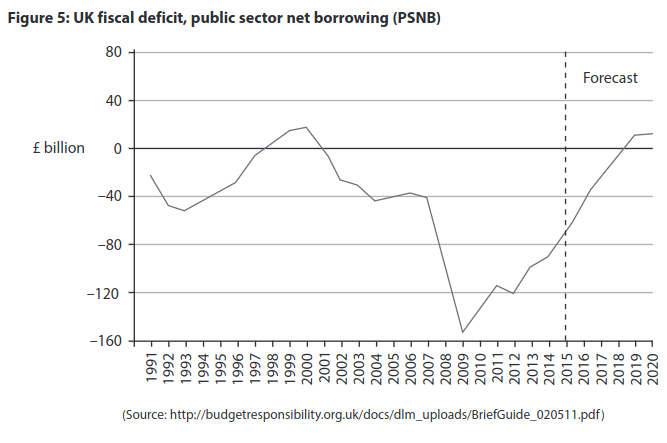

(b) With reference to Figures 4 and 5 and your own knowledge, examine the relationship between the national debt as a proportion of GDP and the fiscal deficit. (8 points)

Mark is an A-Level Economics tutor who has been teaching for 6 years. He holds a masters degree with distinction from the London School of Economics and an undergraduate degree from the University of Edinburgh.